Consciousness

-

We can only be conscious of brain content that can in principle be remembered. Especially, we cannot become conscious of the many processes going on that occur for example to process the sensory input leading to our final realization of reality. Only the result of these processes can be remembered and can become conscious, not the processes themselves.

-

We are not able to remember things in a way that we can freely recall them, if they have not previously been conscious.

-

Consciousness is just that brain content, for example ideas and thoughts, that are transferred in the direction to our permanent memory, where we can later freely access this content.

-

The active impression of consciousness only results, because the active unconscious leaves no traces that can be remembered and because of the intense interactions between active unconscious processes and conscious remembered content.

- Feelings are feedback from our body or the unconscious to our remembered conscious. This feedback has to become conscious, because otherwise no lasting effect or intentional action could be induced by the feelings. This also solves the 'hard problem of consciousness' posed by David Chalmers.

To grasp consciousness, two questions can be asked:

- Can we be conscious of something, which we in principle cannot remember?

- Can we remember something, which has not been conscious before?

In this discussion memory shall be regarded as our random access memory (RAM), from which we can deliberately recall remembered content. An example of content stored in this RAM is typically what one had for lunch yesterday or when to meet the friends tomorrow. This memory is also permanent since we remember many things also tomorrow, which we remember today. Thus, this memory shall be called pRAM here. The permanence is of course not perfect, since we tend to forget things, possibly some even very quickly.

The first of the questions above has to be answered with no. All content of our brain, which constitutes our unconscious, is called unconscious exactly because we can not access it in our pRAM. So, brain content that we can not remember is unconscious. Only that brain content, which in principle can be remembered, can become conscious.

The answer to the second question is no as well. At least I cannot remember content of my thoughts, which have not previously been conscious. For example, if I try to remember the color of a house that I passed by when I drove to work yesterday, I will only be able to retrieve this from memory, if I focused my attention to that house and became conscious of its color. Otherwise I may reconstruct from previous experiences some vague idea of its color, but this would not be a directly remembered impression. On the other hand, feelings I had in a specific situation may come up again every time I remember this situation. But these feelings will not be randomly accessible and thus content of my pRAM unless I have become conscious of them.

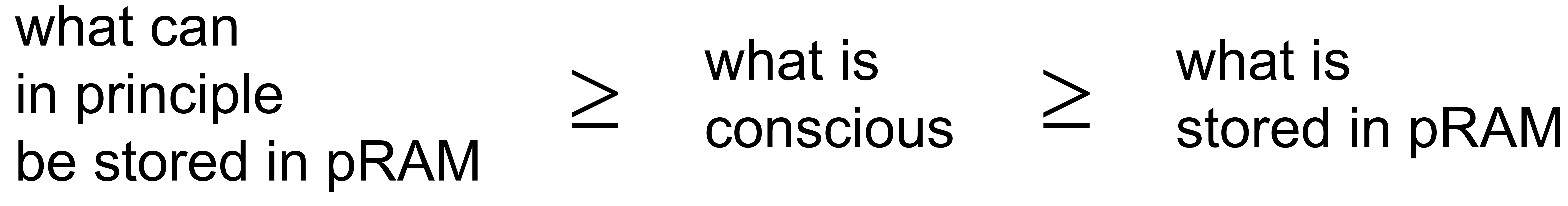

This shows that the following equation can be written:

The larger-equal sign indicates in each case that the expression to the left includes more than the term to the right. This shows, how closely consciousness is related to pRAM. What becomes conscious is thus just between what can in principle be stored and what finally permanently winds up in pRAM. Thus, consciousness appears to be just what is sent to pRAM. If this working hypothesis is followed, a variety of statements on consciousness can be inspected. Being conscious just means that in that state thought content is sent to pRAM, which can later be recalled. Becoming conscious of some sensual perceptions just means that these perceptions can later be recalled from pRAM. Being able to consciously breathe just means that I can remember that I controlled my breathing. Consciously deliberating about something just means that we can remember the sequence of thoughts we had and the final outcome. All these statement appear to be a proper way of describing the situation. Thus, understanding consciousness as what is sent to pRAM memory appears to be an appropriate picture. This view of consciousness also very naturally allows to understand experimental findings that indicate that the becoming conscious follows roughly a third of a second after the triggering event in our brain. This has been shown for example in various experiments by Libet in the 1970s, who had people pressing a button while recording their brain activity with an EEG (electroencephalography). He regularly found that he saw the clear indication of a decision to press the button a third of a second before the person reported that they consciously decided to do so. Of course the decision can only enter pRAM after it has unconsciously been made.

The active impression we have of consciousness, which is so dear to us, thus appears to be an illusion. The active part of our brain are the unconscious processes, which themselves leave no traces that can be remembered. These processes convert for example our primary sensory nerve impulses into impressions and meaning, which is the outcome of these processes, which can be remembered. The processes themselves cannot be remembered. The active impression on one hand results from the active interaction between our pRAM and our unconscious, which continually accesses the pRAM. On the other hand it is a result of a property of our brain, which can be understood from the so-called rubber-hand illusion. In that experiment, of which various videos exist on YouTube, a person is sitting at a table with both hands on that table. The view at one of the hands is blocked with a screen and a rubber hand placed visibly beside the shield close to where the actual hand is located. Some type of sleeve is then draped between shoulder and rubber hand to create the illusion of a connecting arm. The experimentalist then strokes the visible rubber hand and the invisible real hand with a brush in an identical manner. After a short time the person sitting is then starting to mistake the rubber hand as the own hand. This effect is caused by the visual impression overriding the body feeling. Thus, if our brain can not fully make sense of the sensual input, it takes the second-best option as being real. The same occurs, if we ask about the active part of our brain. Our active unconscious, of which all the ongoing processes themselves don't leave any traces that could be remembered, looks around in our skull and can not see anything besides the pRAM. The unconscious can not see itself. The only entity that can be realized are the memories, because only these leave traces beyond the short time span of the now. This pRAM is then taken as the active part of our brain, even though it is just the filing system.

Other models of consciousness, which have been proposed, thus include certain aspects of the unconscious, for example the processes, which lead to a thought becoming conscious. It is believed that a clear distinction as proposed here will allow a clearer analysis. The consequences of this distinction will become more obvious in the following points.

Here, also the interrelation between feelings and consciousness can be discussed. Feelings stem for example from our bodily sensations or may be triggered from situations we are in, where we e.g. feel joy or fear. The question has then been posed, why feelings feel the way they do. This question has been termed the 'hard problem of consciousness' by David Chalmers. To make the question a little clearer, Chalmers asked what the difference would be between us and so-called zombies, who acted identically to us but would not have these direct feelings. I once knew a partial ‘zombie’, who was a classmate at high school. He could not feel his stomach and was never hungry or saturated, but had to eat supported by clock, scales, and a calorie table in mind. This shows that our feelings are the direct communication of our body with our consciousness. Feeling hungry induces immediate action but the feelings also have to be remembered, because otherwise intentional action for example to obtain food would not be possible. Thus feelings have to be conscious, because otherwise they would not lead to any lasting impact. The same applies for feelings induced by situations, where the feelings result from our unconscious evaluation of the entire situation. These feelings are often first unconscious. As unconscious input they can affect our immediate decisions and actions, but they can only be of lasting consequence, if they have become conscious.

While we can survive with clock, scales, and calorie table without the feeling of hunger, it is obvious that our predecessors in evolution, who did not have such means, would have quickly died out. While for us it would have a meaning, if in case of hunger the word ‘hunger’ would pop up in front of our internal eyes, this would have been meaningless to our predecessors. Thus without feelings, zombies could not have developed further by evolution and we could not have evolved. Thus, if our predecessors would have been zombies as proposed by David Chalmers, we would not have developed with our feelings. Either the predecessors would have died out or we would have other means to receive the bodily feedback. The question on the other hand why a certain feeling feels exactly the way it does and not differently, is asking for a cause, where no cause can be specified. The random steps during evolution led to pain feel like pain and not like some itching. It could have been a different feeling instead of pain, but the random sequence of evolutionary steps chose to lead to pain feel like pain. Thus asking for a cause in this context poses a question in an inapplicable category.

|

|

|